Miriam: Enemy of the State

A Mother's Song of Rebellion

Apart from Jesus and Santa Claus, no figure looms larger in the Christmas story than Mary. (Now that I’ve got that sentence out of the way, I’m going to use their Hebrew names—Yeshua and Miriam. I won’t be mentioning Santa Claus again, so I don’t have to figure out his Hebrew name.)

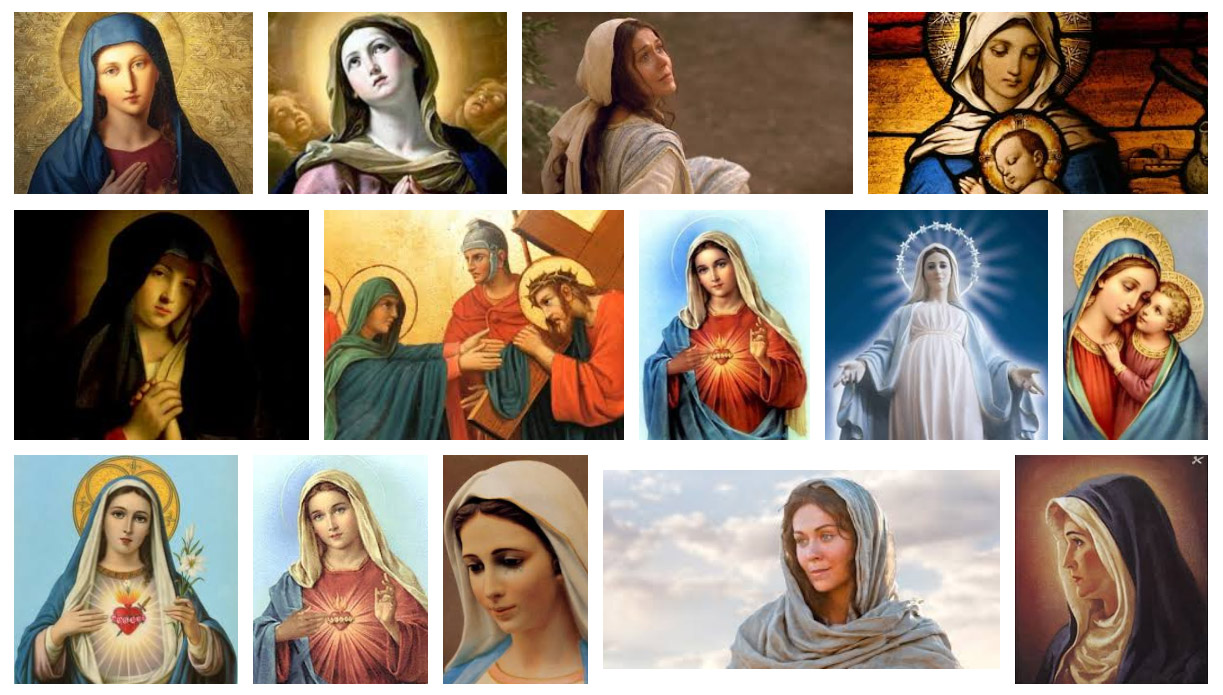

Let’s talk about Miriam. What adjectives come to mind when you think about the much-loved mother of Yeshua?

Meek and Mild? Perfect and Pious? Submissive and Serene? Those are the descriptors that might occur to anyone doing a Google image search for “Mary Mother of Jesus”. See for yourself:

Some of these images make me want to add Sad and Sleepy to the list.

Traditional artists have promoted these attributes, and traditional musicians have backed them up. “Maiden Mother, meek and mild, guard, oh guard thy faithful child.” Think about it: Why is Miriam being lauded and venerated? For her passivity. For meekly submitting to the purpose of God in her life. For receiving the overshadowing of the Spirit. For going along with Yosef to Bethlehem. For guarding the “faithful child” to adulthood. Miriam is seen as a vessel through which God works. And the best kind of vessel is a passive one.

But is this really what God was looking for in a mother for his Son? A pious wallflower with no will of her own? To answer that question, let’s look at the only substantive example of Miriam‘s self expression: the Magnificat (click to read it in full).

Here Luke’s gospel gives us one of the most famous songs recorded in Scripture. It is Miriam’s spontaneous outpouring of worship in response to the revelation of God. Although we don’t know what the music would have sounded like, many composers have set the words to tunes of their own. Often those tunes are delicate, inoffensive melodies that well-suited for the quiet vessel of our Lord. Think “Ave Maria” or “Away in a Manger“.

Those are perfectly pleasant songs, but is that really what it would have sounded like? A closer look at the text might suggest otherwise.

It begins with a recognition of Miriam‘s own newfound condition. She was about to become pregnant, by a miracle of the Ruakh HaKodesh, and not by a husband. She would be fortunate enough if Joseph believed all this, but there was no reason to expect anyone else to. There’s nothing sweet or pious about this turn of events. On the contrary—it’s a scandal.

Is this what Miriam had imagined for her future? Is this what a life of righteousness gets you? To be branded a filthy adulteress by everyone who’d once admired you? None of us would blame her for being afraid or bitter at this point, but instead she declares, “the Almighty has done great things for me.” She believes, no matter what her neighbors think, that all future generations will call her “blessed”.

She doesn’t dwell on herself, though, because something much greater is happening: the Messiah is coming! For centuries and centuries her people had endured discouragement, defeat, oppression and ridicule, waiting for a Rescuer to appear. And now? The moment had arrived.

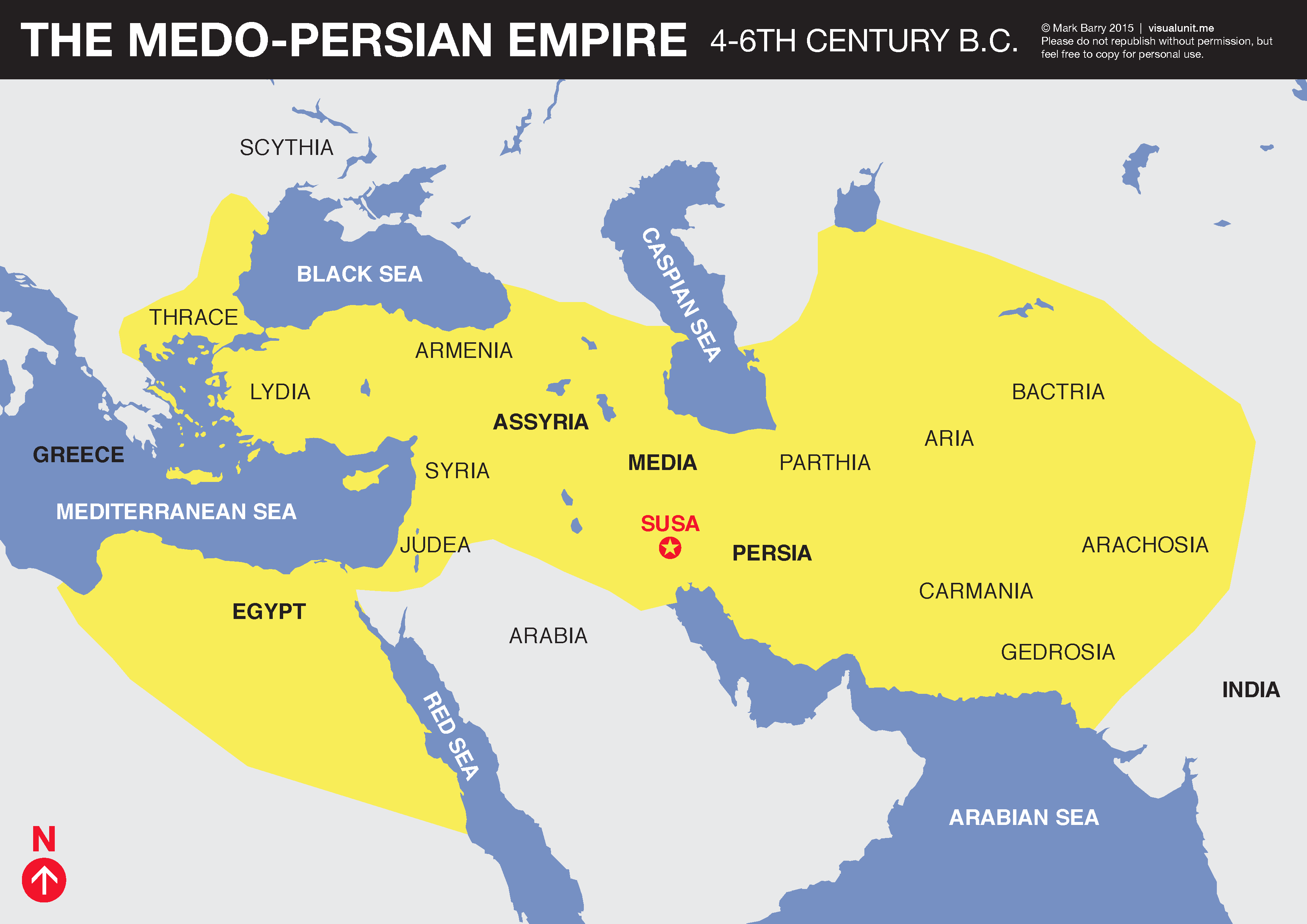

By that token, there’s a danger that Miriam‘s song might be viewed as nothing more than nativist fervor. But it’s so much grander than that. Remember, every nation and city-state had its local deities, but Israel was supposed to have the One True God. Every Jewish blessing begins by referring to God as the Ruler of the Universe. That means that every conflict with a foreign power was not “my god vs. your god”, it was “the Real God vs. the impostors”. Imagine if I claimed my football team was the only true football team—the inventors of football, the keepers of all rules and records, and the scouts and trainers of every other player on earth. If this is my claim, then my team had better win the Super Bowl every year, or my reputation is in big trouble.

But Israel wasn’t winning anything. In fact, they’d been losing ground ever since King Solomon died. Not only that, the players appeared to have taken some sort of extended leave. For 400 seasons. Not a great move for the One True Team.

Nevertheless, the promise lived on. It was the promise to David, to restore his throne and establish a new Kingdom for all eternity. It was a reminder, not only of a time when David was crowned as the King of Israel, but when God was exalted as the King of the Universe. And this promise endured in people like Simeon and Anna, in Zechariah and Elizabeth, in Joseph, and in Miriam.

So what was the Magnificat, really? Was it a lullaby, or a battle cry? I believe it was the latter—more subversive than submissive. Best sung, not with a delicate hand on the heart, but a clenched fist in the air. It is sweeping and epic, declaring the earth-shattering work of God in every generation. Indeed, God has worked wonders in the past, God has looked with favor on his humble servant in the present, God will keep his promise to his children forever. And how will he do it? By overthrowing mighty kings. By reducing vast empires to rubble. By stripping down the wealthy and lifting up the poor.

Miriam’s newfound reputation as an adulteress will place her among the shunned, and she knows it. But that’s not shameful enough for her. She takes her cue from King David, when he says “I will dishonor myself even more than this.” (2 Samuel 6:22) By calling publicly for Caesar to be overthrown, and every human empire to be demolished, she becomes not just a social outcast, but an Enemy of the State. (In case you haven’t noticed yet, the name Miriam is Hebrew for rebellious.)

What does this do to you? How does this change your celebration of Christmas? When you look at the nativity, will you continue to see a collection of angelic sojourners floating two inches above the ground? Or a gritty band of iconoclasts, determined at all costs to launch a global conspiracy of grace?

Back to the song. What might the Magnificat really have sounded like? Here’s a better question: what would it sound like if it were penned today?

Never Alone by Barlow Girl

Imagine Miriam belting this out between a Fender P-Bass and a Marshall half-stack. “We cannot separate / You’re part of me / And though you’re invisible / I’ll trust the unseen” Note: This link takes you right to the chorus, but it’s worth backing up to hear the disillusionment that must have arisen from Israel’s 400 years of prophetic silence.

Feel Invincible by Skillet

Simeon prophesied to Miriam that “Behold, this One is destined to cause the fall and rise of many in Israel, and to be a sign that is opposed, so the thoughts of many hearts may be uncovered. And even for you, a sword will pierce through your soul.“ (Luke 2:34-35) What kind of chutzpah do you think it took for Miriam to receive this promise? In the end, she took the sword to her soul and didn’t fall. “Here we go again / I will not give in / I’ve got a reason to fight / Every day we choose / We might win or lose / This is the dangerous life”

The One and Only Jesus by Propaganda

Perhaps the Magnificat, if written today, would not be a song at all, but slam poetry. (After all, both Scripture and slam poetry are intended to be read aloud, not silently.) Listen for the heart of Miriam in this work by Christian rapper Propaganda: “the greater revolution / earthly kingdoms are pitiful // for the joy set before him / this kingdom works backwards / the ruler serves / servant king / suffering servant / sit with that one”

Moving forward from December 25, let’s ask this together: What is the point of Christmas if not to discover the Spirit of Christmas? And what is the Spirit of Christmas if not the Spirit in Miriam—the Ruakh HaKodesh empowering her to take the heat and bear the burden? To receive the sword to her soul and bleed for what she believes? This is not passive piety, but active resistance.

No matter what party is in power, or which side of the “War on Christmas” appears to be winning, the Spirit of Christmas is always treacherous, always counter-cultural, and always invincible. May it be so in you and me.

TOPICS: Christmas, Magnificat, Mary, Miriam, Song