Purim to the People (Part 1)

God Save the Queen

Host: Hello and welcome back to Good Morning Persia! I’m Kevin Adar. Today we’re delighted to be joined by our very own Queen Esther. Your Imperial Majesty, thank you for being here.

Queen: The pleasure is mine, Kevin.

Host: Allow me to ask the burning question, Your Highness. You have been credited with remarkable acts of bravery in the royal court, resulting in the deliverance of every Jew residing in our great empire. And now you’ve had an entire book of the Bible devoted to your story, and named in your honor.

Queen: That doesn’t sound like a question, Kevin.

Host: Here’s my question. Do you consider yourself a Spiritual Hero?

Queen (glances off-camera at Mordecai, who is waving his arms and mouthing “NO”): Of course not, Kevin. I only did what any secretly Jewish Queen of a heathen empire would have done.

Host (smiles broadly): Well said, your Majesty. Now we may officially call you a Spiritual Hero.

Queen: Wait, what?

It’s Purim season, you guys. And as some of you may know, it’s a Purim tradition to recount the story of Esther with a touch of whimsy. But in the rhetorical vehicle offered above (did you LOL?) there’s a serious question riding shotgun: Should we consider Esther a Hero of the Faith?

To hear most Bible teachers and preachers tell it, the answer is a simple Yes. Although Esther is the only book in the Bible which doesn’t explicitly mention God, prayer, or any other religious rite, the book is nevertheless canonical. And if a story is in the Bible, its protagonist must be a model of godliness, right?

Except for Jonah, of course. And… I guess Adam & Eve. Then there’s Abraham and Jacob, who mess up a lot at the beginning. And David and Solomon go off the rails pretty hard at the end. Noah, too. And don’t forget Moses.

Sometimes the behavior we read about in Scripture really is commendable, and sometimes it’s not. More confusingly, God often blesses and supports the protagonists, even when they could have done way (way) better. But before we get too far ahead of ourselves, let’s circle back to Esther.

In case you’re not familiar with the story, here’s the “tl;dr” summary:

King Xerxes, Emperor of Persia, holds a beauty pageant to pick a new queen for himself, and Esther wins the tiara. (Yes, it’s crude, but this was before dating apps.) Esther, a Jewish orphan, is urged by her cousin and adoptive father Mordecai to conceal her ethnicity for her own safety. But then Mordecai manages to anger the King’s prime minister Haman, who responds by tricking the King into decreeing that all Jews will be slaughtered on the 13th day of the month of Adar. Now it’s really dangerous for Esther to reveal her Jewishness, but she eventually does so anyway, in a plea to the King to save her people from the impending genocide. In the process, she accuses Haman of conspiracy, and the King has him executed almost immediately. Then the King agrees to arm the Jewish people across the empire, and they successfully defend themselves against all attackers. The next day, they throw a giant party.

To mark this overwhelming victory, Purim is established as a holiday to take place on the 14th and 15th days of Adar (Feb 28 – Mar 1 this year.) So what should we do about it? Throw a giant party of course! (Where’s a hamantasch emoji when I need one?) It’s time to take full advantage of the costumes and snacks and jokes and games, especially if you need an alternative to Halloween.

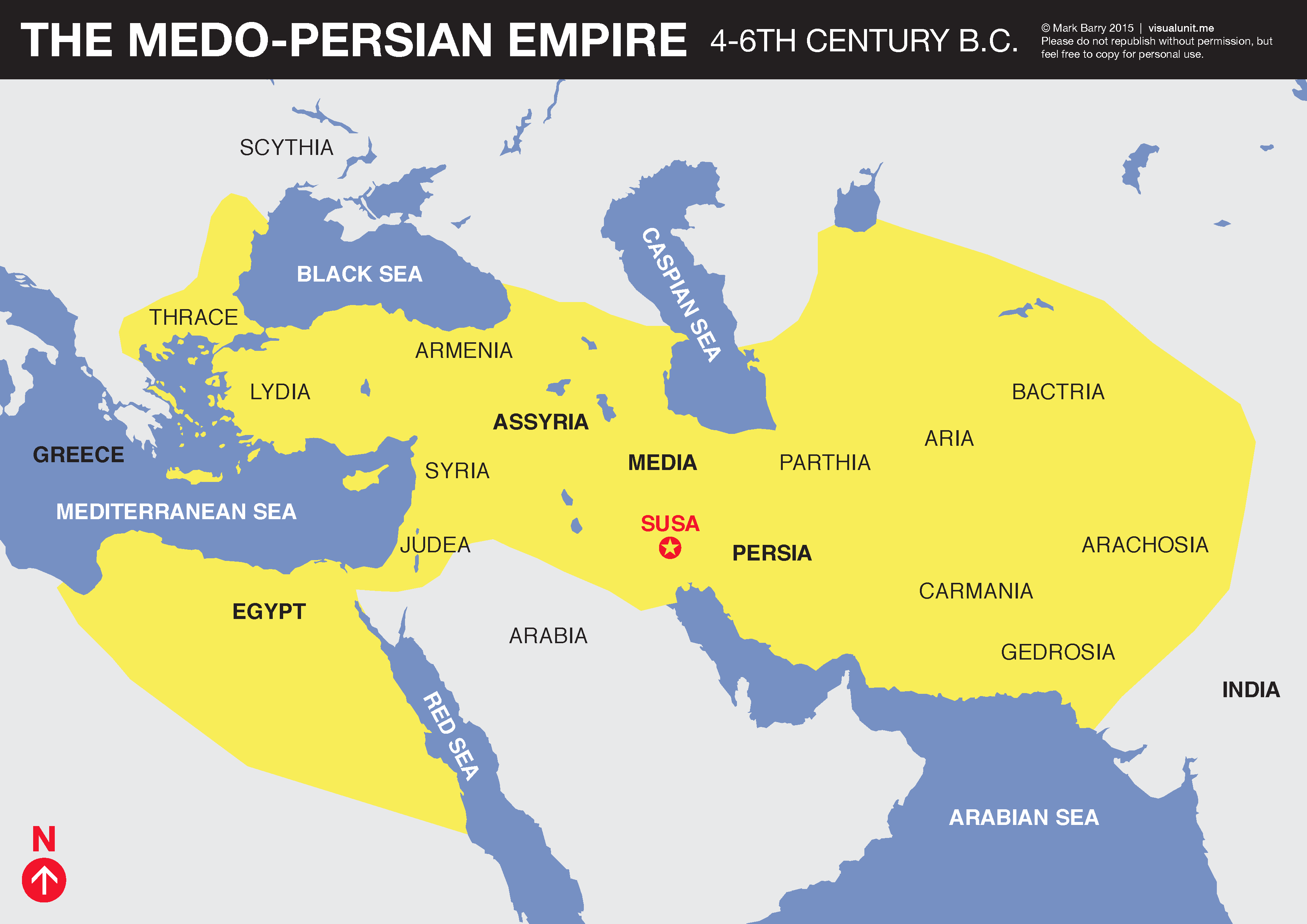

If you’re Jewish, the occasion is a no-brainer. You descended from someone whose life was saved by Esther and Mordecai’s intervention. At the time of Esther, virtually all the Jews in the world lived within the boundaries of the Persian Empire (map it). Even those who had recently traveled back to Jerusalem to rebuild the Temple were implicated. So Haman’s decree really did spell the end of the children of Israel.

But if you’re not Jewish, you might ask yourself, what are we really celebrating here? And why is the book of Esther even in the Christian Bible? (You wouldn’t be the first to ask this.) The reality is, despite the wishful thinking of the aforementioned Bible teachers and preachers, we don’t really know if our protagonists were Spiritual Heroes. It’s possible that they weren’t even spiritual people.

Would this be so hard to accept? After all, how righteous were the Hebrew slaves in Egypt? Was Moses even a man of great faith before the Burning Bush encounter? All the scriptural signs point to No. Moses and the Hebrews were no doubt decent people, but they were not quick to understand what God was doing for them. They were too far from their roots, both in time and space.

With the Exodus experience and beyond, the children of Abraham found themselves on a steep learning curve to accept the sovereignty and faithfulness of the God of Abraham. This is why God calls them a “stiff-necked people”, and also why he reminds them over and over, “I will be your God.” In the process, not only do they come to understand who God is, but also who he’s created them to be.

Slavery in Egypt had robbed the Hebrews, not just of their freedom, but their identity. And hundreds of years later, captivity in the East was threatening to do it again. It’s painful to consider that the Jews in our story might actually be ungodly, but it makes sense when we read about their behavior. Mordecai is convinced that Esther is their people’s only hope, and he has to persuade her that her own life is in danger before she will stand up to Haman. When hearing bad news, Mordecai mourns, but doesn’t cry out to God. When Esther prepares to intervene, she calls the people to a time of fasting, but not prayer. And when they achieve victory, they establish a day of feasting and gladness, but not praise and thanksgiving (as far as we know.)

Of course, I could be wrong. It’s possible that a strong faith in these characters really is written between the lines. But it’s not necessary to believe this in order to get the message of the story loud and clear. And what is that message, exactly?

I believe the story of Esther is telling us that the covenant belongs to God, not to people. God doesn’t rescue us, heal us, or bless us as a reward for our faithfulness. Rather, God acts on our behalf because of his great mercy. Because of his faithfulness to his covenant promises.

Whenever we hear of a tremendous blessing, or divine intervention, as humans we want to look back, and ask ourselves what the people involved must have done to deserve it. (So we can emulate them, of course.) But if we examine the various scenes of God’s favor and deliverance throughout Scripture, it’s easy to see that God isn’t looking back, he’s looking forward. So we should be asking, not what were the characters like before the event, but after.

In the story of Exodus, it’s clear that God is playing the long game—creating a nation from scratch. And eventually, through many great miracles and blessings (and fits and starts) that chosen nation comes into its own. So if we can accept that the great miracle in the story of Esther is actually a divine stimulus instead of a divine response, what was the result? Did it work?

Come to think of it, what ultimately became of Esther, Mordecai, and the Jews of the Persian Empire? Where’s a sequel when we need one?

I’m glad you asked: Purim for the People (Part 2)